Milton Aalen learned responsibility early. It was a family trait. His father, a career military man, who had moved his family to San Antonio, died when Milton was 12 years old and his older sister worked to support the family until Milton graduated from high school in 1939. Then it was his turn. With about two months of business school under his belt, he went to work at Duncan Air Depot, later Kelly Field, to support the family, and in a few years, moved up to Supervisor of Meteorological Supply.

But, there was a war on and Milton realized he would soon be in it, so he volunteered for the service he wanted. Aalen was in love with aviation.

In June of 1943, he volunteered and signed up for the Army Air Corps aviation cadet program; he wanted to fly.

The Army Air Corps cadet program had two training centers, one in San Antonio and one in Santa Ana, California. “OK, great!” he thought, “I’m already here,” thinking he could stay in San Antonio, and before he knew it, he was off to Santa Ana, CA.

He went through basic in Santa Ana, and it did have one unanticipated advantage. “I got to dance with Linda Darnell.” (For those of you who are too young to remember, Linda Darnell was a particularly gorgeous movie star of the 1940s.) Aalen added that he did not get to dance with her for long—there was a long line of cadets waiting for their chance.

After basic, Aalen was transferred to Thunderbird Field in Arizona. There, he had a flight instructor who was not committed to his success. In fact, he seemed committed to the opposite. Even though Aalen learned how to do the loopty-loops, he washed out when his Stearman airplane wing tipped and hit the ground, “resulting in a ground loop.” Therefore, even though he had completed his solo flight and logged about 40 hours and “enjoyed flying and acrobatics,” he was out.

The Army sent Aalen to Sioux Falls, SD, to become a radioman. It was the winter of 1944 and bitterly cold. Trainees hustled out from under their covers at 3 am for training. But, in February 1944, he was suddenly sent to Laredo, TX to become an aerial gunner. “The training was actually a lot of fun,” said Aalen, “as it mainly involved learning to lead from a moving vehicle and airplane.” He explained that, when gunning from a plane, you actually have to shoot behind the target since the plane is moving away. He was back in the air.

Aalen was sent to Fresno, CA, for a short stay and then to Tonopah, Nevada, where his ten-man crew was assembled and given their new B-24 Liberator, the four-engine heavy bomber that was about to help soften up Nazi resistance for the invasion of Europe. The crew was supposed to pick up their bomber and head for England but the plane was faulty. It “would not trim or fly correctly” and they had to leave the plane in Midland, TX.

From there, Aalen went to New York City where he stayed in the Waldorf Hotel for two weeks. With Aalen, it seemed that every disappointment was soon reversed.

After his Waldorf stay, Aalen was put on a troop ship bound for Northern Ireland, mostly filled with Army infantrymen and WACs. The WACs were separated from the Army men, but wouldn’t you know, Aalen was given the job of chaplain’s assistant, and he was able to move around the ship freely. He remained in contact with some of those women of the Women’s Army Corps during and even after the war was over.

Two days into his stay in Northern Ireland, Aalen caught a “gooney bird,” the nickname for the C-47 transport plane, and was airlifted to Horsham St. Fate at Norwich, England—his headquarters for the rest of his tour of duty. “As the base was a former RAF airfield, we were assigned to permanent-type barracks with wooden bunks and straw mattresses which were good accommodations comparatively speaking.” The straw could get tickly, but most of the time, say Aalen, “If you were tired enough, it didn’t bother you.”

On June 7, 1944, he found himself in another crew’s Liberator in the “waist” section, flying over Normandy the day after D-Day. The regular gunner was sick and Aalen got the call to fill in as waist gunner.

Artillery fire was intense on the ground below, and Aalen mentioned to the pilot that it looked like they were really mixing it up down there. The pilot indicated that he (Aalen) was not seeing the situation exactly right. “It turned out to be anti-aircraft guns shooting at us!” Moreover, Aalen was introduced to flak, the Liberator’s most serious threat, first hand.

“The flak was pretty heavy but we only caught a few holes in the wings.” It was Aalen’s “baptism of fire” – an experience he might have delayed if the gunner had not been sick in bed.

June 7 was the first of Aalen’s 50 missions over France and Germany. Thirty-five were combat sorties; fifteen were supply missions to re-fuel Patton’s tanks.

On combat missions, Aalen’s 458th Bomber Group, 754-squadron, hit targets like refineries, factories, marshalling yards (train stations), bridges, airfields and communication centers. The most difficult targets were those in Berlin and Munich because the return trip was so long—more chances for anti-aircraft fire to hit them. “They were very accurate too.” Munich was heavy guarded, and Aalen remembers one bombing run on a train-switching yard through particularly heavy fire. But, they made it. “It was a magic time.”

The 458th was engaged in daylight precision bombing—a very hazardous business early in the war. The U. S. Army Air Corps bombed during the day, the RAF at night.

On those sorties, Aalen served as tail gunner, waist gunner or nose gunner, but he never actually shot at an enemy plane. The bombers flew in tight formations of 12 (painted strips on the tails of each Liberator would tell you if you were in the right group), and Germans could not handle such concentrated fire. They would wait until a plane had a problem and had to drop back. Then they would pick it off.

Aalen’s plane lost an engine over Belgium on one sortie, but, fortunately, they were close enough to home base that, even though they were a sitting duck in every sense of the word, they were not picked off. The crew threw out what they could to lighten the plane and limped on into England.

But, flak, not enemy fighters, was the real problem. One thing the crew frequently did after they safely landed was count the holes. If they had encountered lots of flak, they would see if the holes in the plane’s skin would break their standing flak record. Aalen remembers 17 as being the ultimate flak-hole record set in one of those missions. He flew in two bombers during his 50 missions– the “Tail Wind” and the “Little Lambsy Divey.” Crews could get pretty inventive when it came to naming (and painting) their planes.

Even though Aalen was not doing any shooting to speak of, he found himself engaged in another activity on occasion that may have been a lot more dangerous to him and the bombing target. Liberators carried 250 lb. bombs with propellers attached. The propellers were actually triggering devises that blew off in the air, beginning the ignition sequence.

Sometimes, said Aalen, those propeller wires would hang and the bomb would not drop. You could not bring your bombs home with you—they had to go somewhere—so someone had to kick the bomb off, out of the open bomb bay doors. The wind was horrendous and the catwalk running between the two bays was only about a foot wide, and you had to make a little leap before you could find something to hold on to so you could kick the bomb off. To top is all off, “you couldn’t wear a parachute.”

“Never look down” was the rule.

The two or three times he had to kick bombs were some of his more terrifying moments. The other came when Aalen was sitting in the nose turret. “A big hunk of metal came through the Plexiglas and, like a ball on a roulette wheel, circled [round and round] the turret and dropped at my feet.” That was the closest he came to being hit.

On a Berlin raid, “I was able to drop the bombs and possibly hit my grandfather’s alleged brewery.” He had heard during his childhood that one of his grandfathers had owned a brewery in Berlin.

Another memorable mission was a sortie over Hamburg, home of the German U-bomb fleet. It was a “booger,” lots of anti-aircraft fire, very heavy flak. “We watched one of our planes take a direct hit with no chutes.” The plane went to pieces—no survivors. That was the mission on which Aalen’s crew achieved their “17-hole” record.

On its 15 non-combat missions, Aalen and crew carried fuel to the Eighth Army on the ground. “The gas was stored on the aircraft in the bomb bay area in large rubber tanks which were unloaded to tank trucks on various airfields north of Paris.”

On Christmas Day, 1944, Aalen’s crew flew their last mission. It was a memorable Christmas. Then it was off to the coast to catch a ship home. The return trip was a lot quicker than the first—a good thing, too, because the WACs were not available on the trip home—but it, too, was memorable. Aalen came home on the Queen Mary, probably the greatest cruise ship of its day.

After a two-week leave, Aalen reentered the aviation cadet program, this time hoping to become a navigator. And, unlike the first time, he was stationed at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. But, apparently, it wasn’t meant to be. On his second time through, he injured his knee playing football and never got to fly over the Pacific.

Instead, Aalen was attached to the Corps of Engineers and “sent to Ft. Lewis at Tacoma, Washington, to learn how to fight forest fires.” After a month’s training, he was sent to Boise, Idaho, where he “operated the radio for the men working in the mountains putting out fires.” His early radio training came to good use.

After several months in the Corps of Engineers, Aalen was discharged and returned to San Antonio. A good friend of his, Ed Tschoepe, was going to Texas A&M University and Aalen decided to become an Aggie as well, thinking he might want to get a permanent commission in the Air Force (after all, he had flying in the blood).

During his college years, he was introduced to Bernadine Wright; they were married in September 1948.

He did not make it back into the Air Force. He made it to Hearne instead. After five years of working for the IRS in Houston, he became administrator of the Hearne hospital. Moreover, that is how he became the first name in the phone book for over 40 years, and, along with Bernie, an invaluable member of the Hearne community.

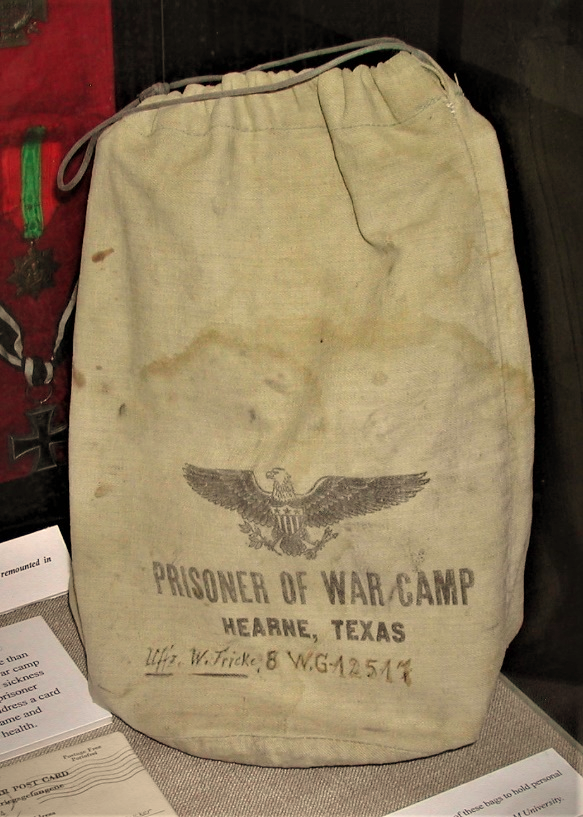

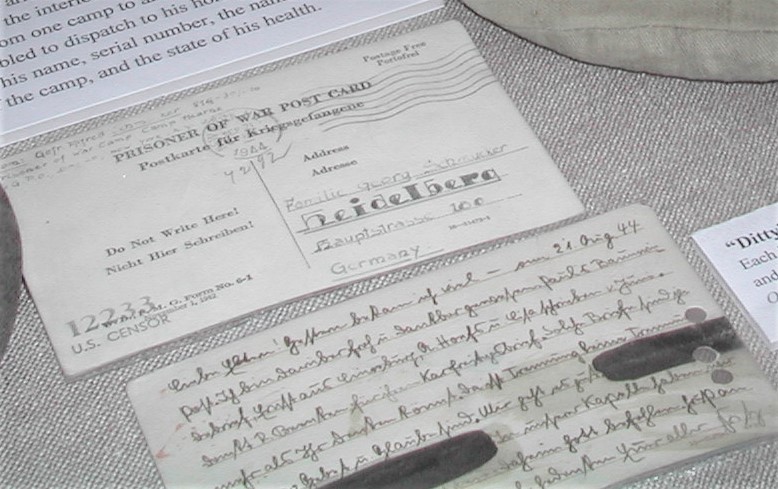

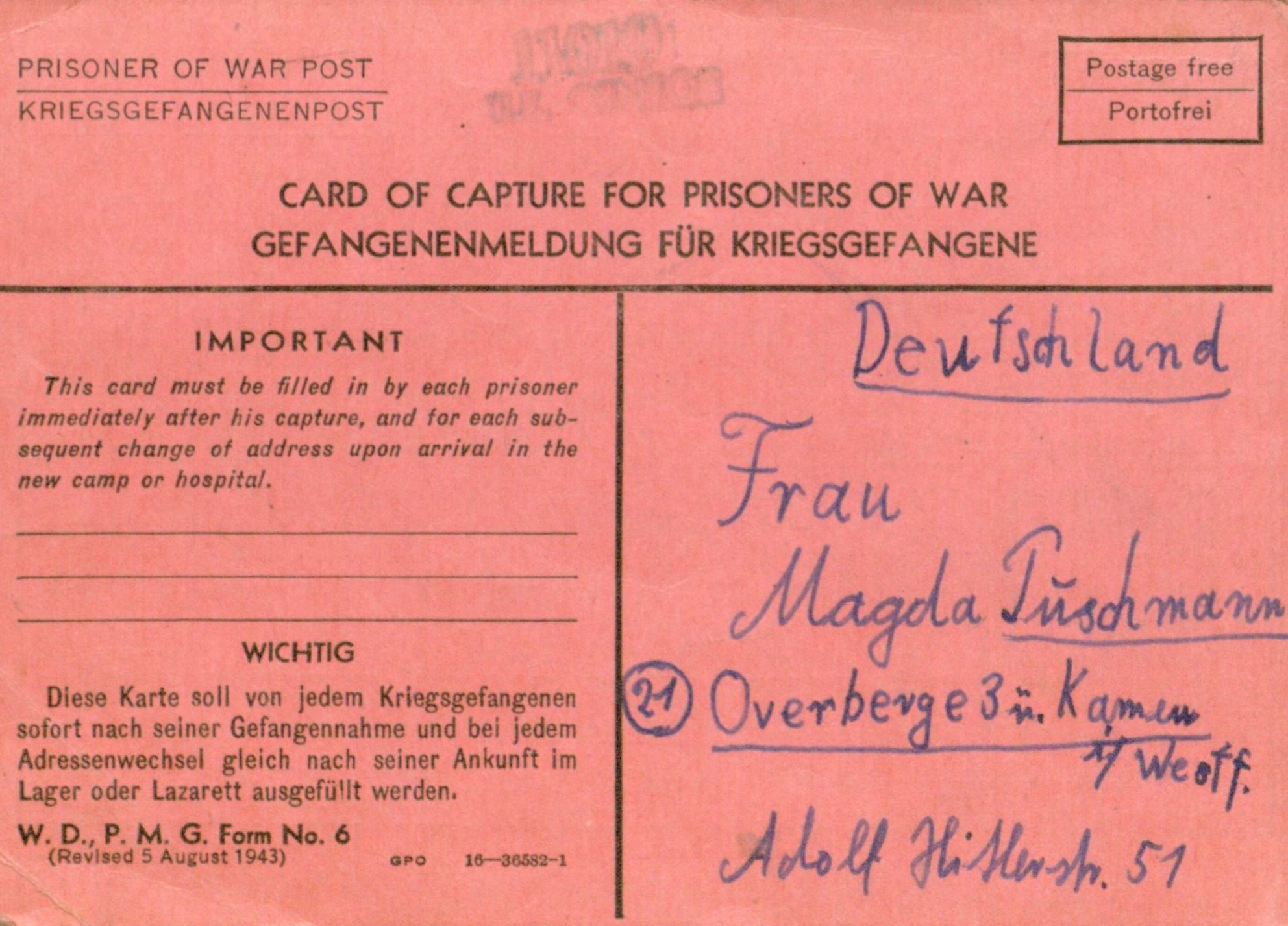

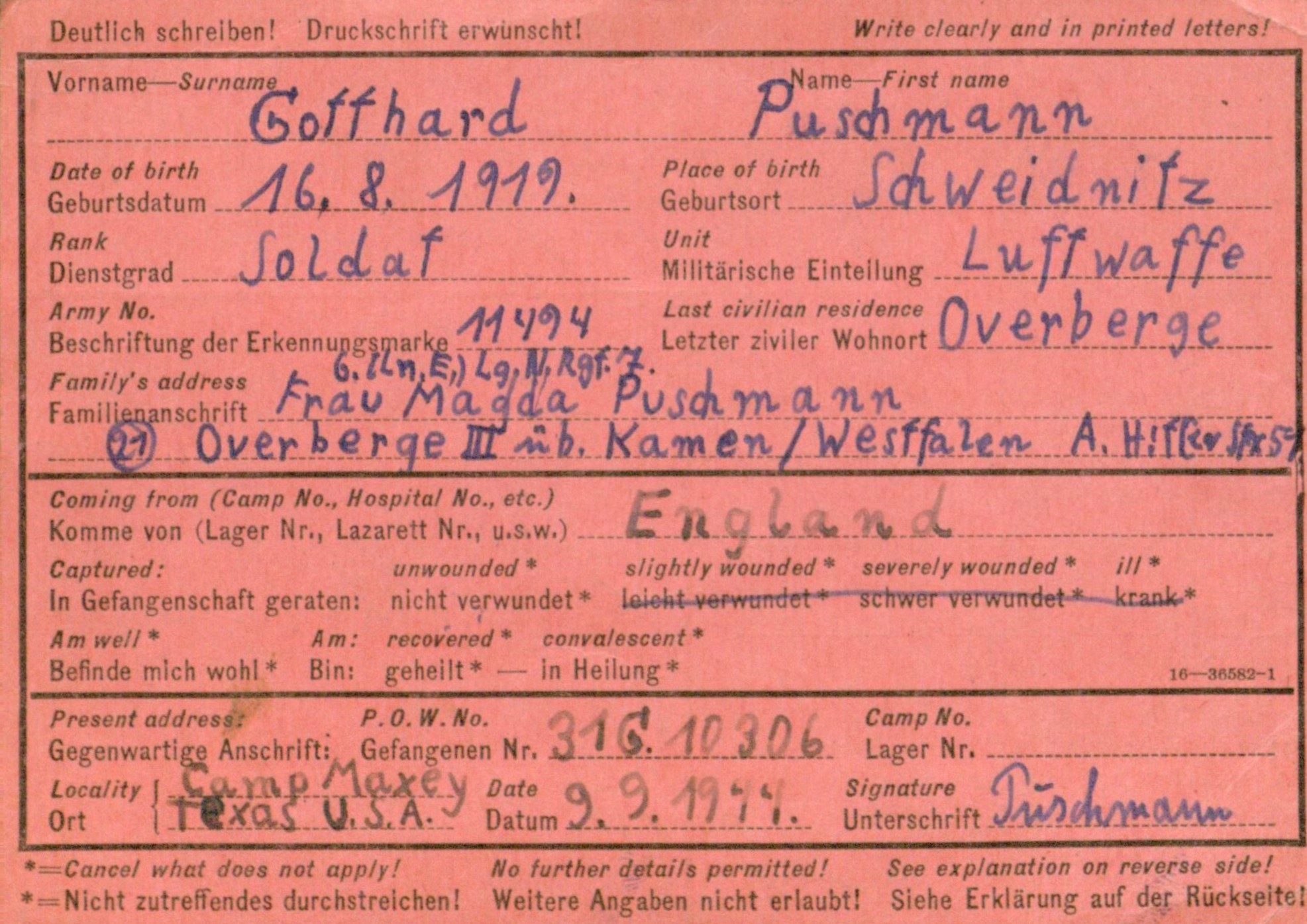

—Card of Capture, Front & Back

—Card of Capture, Front & Back