In World War II, most African-American soldiers were not allowed to go into combat. Many were sent into the Quartermaster Corps where several units gained distinction for lightening-like delivery of weapons, ordinance and food. But, for some like Calvert’s Lorenzo Portis, the Quartermaster Corps translated into combat as they fought the Japanese to deliver their loads.

Portis’ job was to deliver bombs through sniper-invested jungles to an Army Air Corps ammunition dump in the Philippines. From the cargo ship port of entry to the dump, Portis often had to fight his way through 30 to 40 miles of territory that the Japanese had not relinquished. In recent years, he hadn’t thought a great deal about his tour of duty until Katrina and Rita flattened parts of the Gulf Coast. The devastation reminded him of what he had seen in WWII.

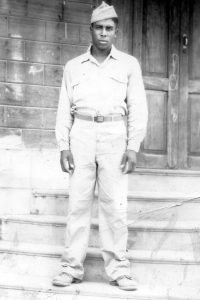

Lorenzo Portis was born and grew up in Hickory Flat on the south end of Calvert, the oldest of 13 brothers and sisters. Though he started school in one of the little church supported primaries in the county, he soon transferred to what is now W.D. Spigner to become a member of the school’s “first” first grade class in 1928.

Living with his grandparents during each school year, Portis stayed with his Calvert class until he left school just short of graduation. He got married and moved to Houston to work because he didn’t want to farm any more. Then the war caught up with him and he was drafted. He brought his wife back home to Calvert and went to San Antonio to enlist.

From San Antonio, he was sent to Ft. McClennan, Alabama, for four months of infantry training that the Army probably didn’t intend for him to use. Several months later, it came in handy.

From Alabama, Portis was sent to Ft. Ord, California, on the Monterey Bay Peninsula, a place many have called the most beautiful military base in the United States. For Portis, it was the jumping off place. He was soon aboard the U.S. Gen. William Wagner headed for the Philippines.

The voyage took 26 days and he was seasick for about three, but after those first days, he adjusted. On board, he met a friend of his from Red Hill just south of Calvert, and they made the trip together.

Within 15 minutes of going ashore at a point just south of Manila, he and a buddy were introduced to the realities of war. “We were sitting on a log and one bullet killed the man beside me and the one behind him – one shot killed them both,” said Portis.

Portis’ assignment with the 3666 QM Trucking Company was to drive a truck carrying two bombs to the ammo dump, turn around, and repeat the trip. The road was frequently booby-trapped and Portis had to wait for the all clear before each run. One time early in his tour of duty, he was held up near the port in a foxhole for three weeks. Heavy bombing in the area prevented him from delivering his load, but life in the foxhole wasn’t much safer. “If you dozed off, the Japanese would come in and cut our heads off,” said Portis. On more than one occasion, Portis saw headless follow GI’s in neighboring foxholes. He spent a lot of time behind a big rock protecting him from heavy enemy fire.

On his 30 to 40 mile runs, Portis frequently had to lob hand grenades into the jungle to discourage enemy attacks. The problem was the timing was off. Before the grenades exploded, the Japanese could throw the grenade back into the truck convey. A few trucks were lost that way. The Army had to shorten the time from pulling the pen to explosion to make grenades US rather than Japanese weapons again.

Though Portis was safer in camp, he wasn’t much safer or free of combat duties. To return frequent enemy fire, he and a partner manned a bazooka. His job was to take the coordinates radioed in from observers in planes above the area and line up the sight.

Portis remembers with fondness a little 12-year-old Philippine boy who came into camp dragging a gun. The Japanese had wiped out his family and probably his whole village and the Americans took him in. One day he started “raisin’ up sand” and pointing at the camp’s water tower. The Americans saw a man up on the water tower but thought he was repairing something. Soon after, the boy took his gun and shot the man off the tower. The GI’s later realized that the man was Japanese and he had been attempting to poison the water and kill everyone in camp. He liked that 12-year-old boy.

“We learned their language,” said Portis, at least the basics. He remembers the gestures for “come in” and “go away” were just the opposite of ours.

Portis sent all but $44 of his small paycheck home each month because he didn’t have as much use for it as his family did. It was too dangerous to leave the camp and go into town.

Despite its horrors, Portis says his time in the service was good. His wife received $121 a month, enough to live on in Calvert during WWII.

After the war was over, Portis drove a bus hauling merchandise over the island because he did not have enough points to go home. When he had enough, he took a ship home to Camp Stormer in California (the trip was only 14 days on the way back) and from California, he traveled by train to San Antonio to be discharged in 1946.

Speaking of his service to his country, Portis said, “I was fighting for my country so it was all right. I’m just glad I lived through it.” After returning home, he attended Veterans’ School in Waco to study mechanics and then shoe repair. He never liked putting engines back together but he liked the shoe business. “I learned how to make shoes. I liked it.”