Among the many activities offered to prisoners of war during their internment at camps across the country, woodcarving was a notable pastime. At Camp Hearne, we have been privileged to receive several woodcarving projects, or what some might call “whittling,” created by prisoners and generously donated to our exhibit.

These carvings vary greatly in terms of detail and craftsmanship; some are intricate masterpieces, while others are more modest in their execution. However, each of these works of art represents a prisoner’s earnest endeavor to occupy their time and make the most of their confined space. Beyond their intrinsic artistic value, these carvings held an additional significance as they became a form of currency within the camp. Prisoners would offer their creations to guards they considered friends or trade them for coveted items like cigarettes, coffee, soap, and other necessities.

Recently, we had the privilege of receiving a remarkable woodcarving project, a hexagonal box, as a donation to the Camp Hearne Exhibit. This unique artifact was generously contributed by Catherine Mottet from Lubbock, Texas.

Catherine’s uncle had served as a guard stationed in Texas during WWII. Before leaving the state, he contacted his niece in Dayton, Ohio, to inquire about any mementos she might want from Texas. She requested a pair of cowboy boots. However, as time passed, she expressed curiosity about whether he might possess one of the inlaid boxes crafted by the camp’s prisoners. He informed her that he had, in fact, held onto a hexagonal box created by a German POW.

For years, Catherine took great care in preserving this distinctive piece of artwork, and she eventually decided that it deserved a place in a museum. We are incredibly fortunate that she chose Camp Hearne as the final home for this historically significant and visually captivating creation.

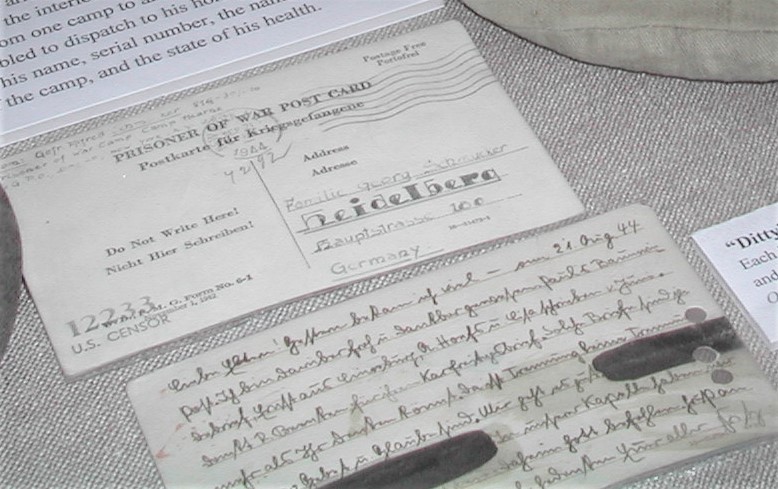

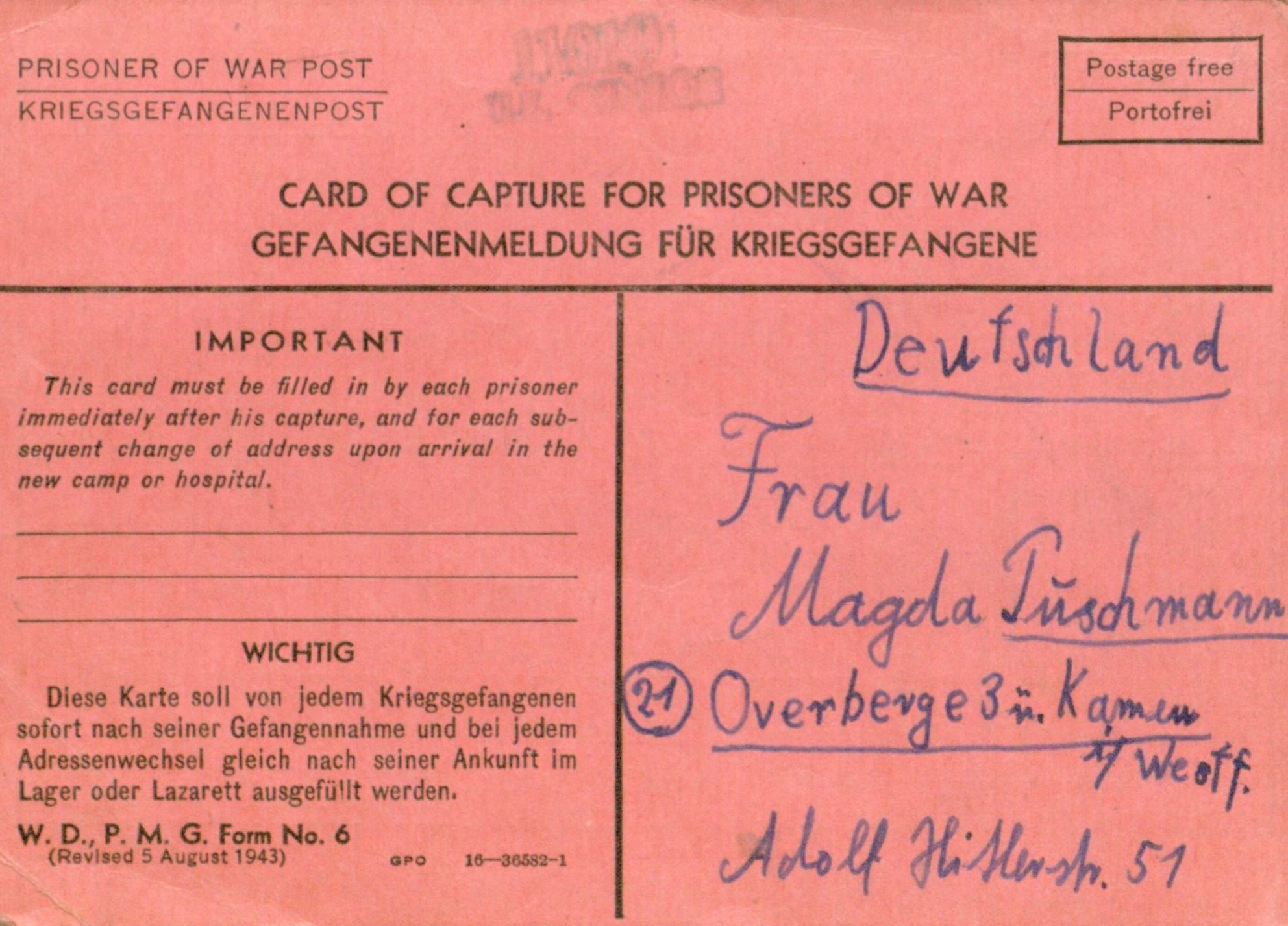

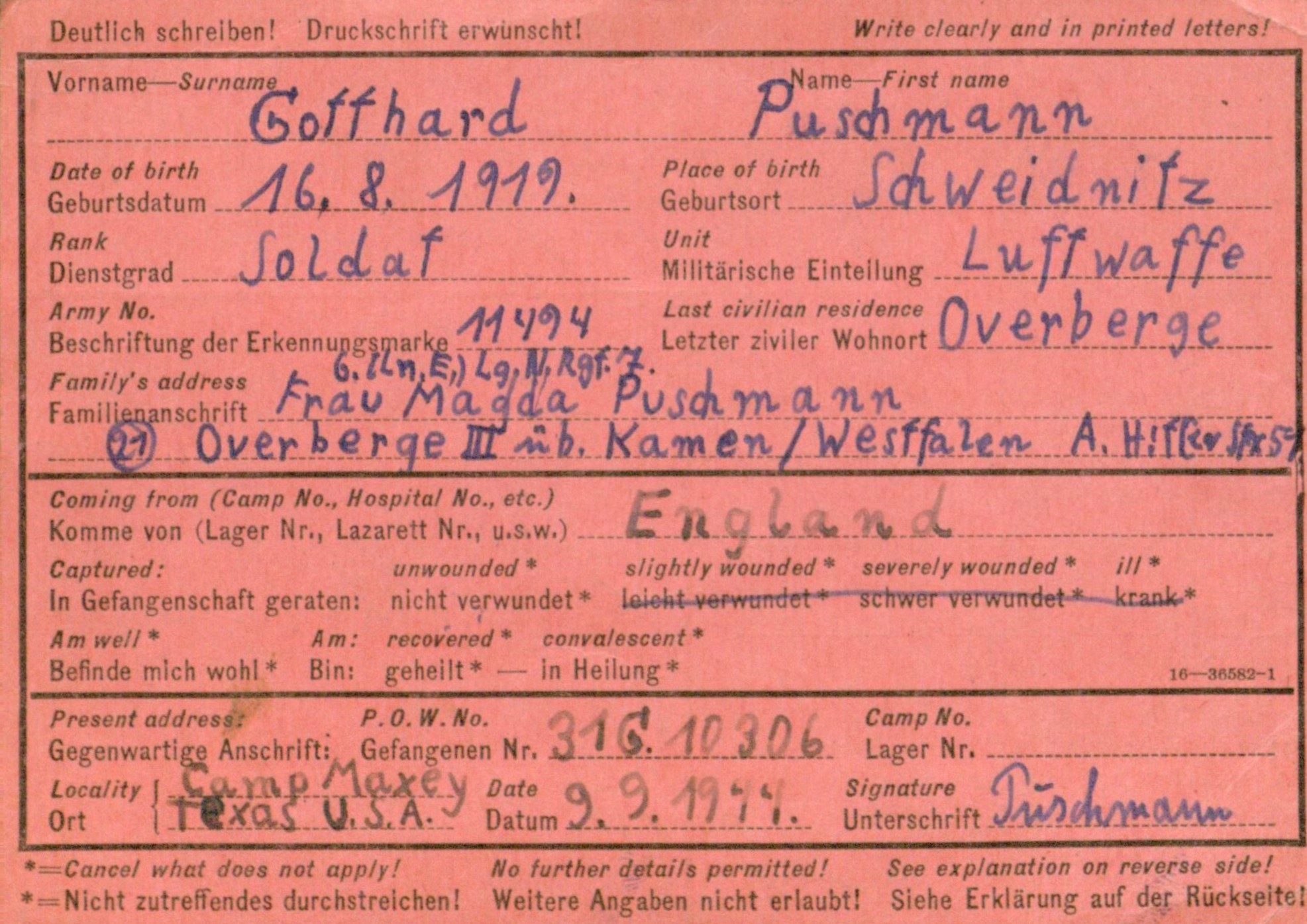

—Card of Capture, Front & Back

—Card of Capture, Front & Back